A New Direction

It has been some time since I have updated this blog, and I think that largely came down to being uncertain with the direction I wanted to take it in. This, ...

This post is a tutorial that will go from a basic introduction to programming, and finish off with writing a simple ORF finder. If you do not know what that is, we will get there.

It is becoming increasingly important in biology to have an understanding of computational tools. They are appearing everywehere and are necessary to analyze data on the scale that biologists are looking at today.

I am writing this tutorial to be run here or here

and all code in this tutorial should work on both sites. To run the code,

type it in and hit either Run or Execute, depending on the

site you decided to use.

If you are a 1337 h@x0r, feel free to use any environment that you are

comfortable with to write and run this code.

Learning to program can often be intimidating, but it really boils down to only a few relatively simple concepts, which when combined in unique ways can perform complex tasks! While other concepts exist, I would argue that there are three major categories that most of these concepts fit into: variables, operations, and control flow. In brief, these mean how we store information, how we manipulate information, and how we tell the computer which, and when to perform, operations on variables. With this in mind, we will get started with writing your first program, then going through applying each of these three concepts in Python.

It is tradition in the world of computer geeks to always write the

famous “Hello, world!” program when you learn a new language, so we will

start with that. Enter the following code into your editor, then hit

Run and pat yourself on the back, with the knowledge that you are

now a programmer.

print("Hello, World!")If you got everything right, your computer printed out "Hello, World!".

Great work! Now let’s get into the meat of coding, now that we know

how to write a program!

A variable is like a box, it stores some item for you. This item can be all sorts of different things, including letters, numbers, or even DNA sequences. Below are a few examples:

an_integer = 42

a_float = 3.14

a_string = "A series of symbols and letters"

another_string = 'Could be written using single quotes in Python'You will notice that each variable created in the same way, name = value.

We are ‘binding’ value to name. Now every time we use the name, it

will act as though we had given the code the value to which it is bound.

Finally, each variable has a ‘type’, which describes what the data is. A

few examples of types are listed below:

integer: Stores an integer… Hopefully this makes sense.float: Store a decimal number, or a ‘floating point number’.char: Short for character, stores a single symbol. Note that the

character '1' is not the same as the integer 1 which is not

the same as the float 1.0.String: A series of characters.Later we will see how to use a string to store a DNA sequence. Whenever you have a piece of information that you want to store and use later, you should put it in a variable. Not only does this make it convenient to access later, it makes it easier to remember what the data you’re storing is! Consider the two snippets of code below:

print(3.14159)As oppose to something like this:

pi = 3.14159

print(pi)Both of these code snippets will do the exact same thing, but in the second, you know exactly what is being printed, the value of Pi!

We have now see how to store single items, but what if we have a collection of items that we want to store? Python has the answer! We can use lists. In fact, a string is effectively a list, but we won’t go into that. Below are some examples of lists.

empty_list = []

list_of_numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4]We can access each item by using the item’s index, starting from 0. Take careful note of this, it can easily lead to mistakes.

string_list = ["item1", "item2", "item3"]

print( string_list[0] )

print( string_list[2] )This should print the following if you run it:

item1

item3

We can also get a ‘slice’ of a list like so:

a_list = [1,2,3,4]

print( a_list[1:3] )Notice that this prints items starting from index 1 (i.e. the second item in the list) up to, but not including, the item at index 3 (i.e. the fourth item in the list). These items are also printed as a Python list, mean we can treat the result of this slice just like we would any other list! For reference, the output of the above code is below:

[2, 3]

As a final note, strings can accessed in the same way. For example, we could get the first three letters of a DNA sequence like this:

dna_seq = "ATCGTCGTGATGCATGCA"

print( dna_seq[0:3] )This should print ATC. This will come up later.

Variables are great and all, but they aren’t particularly useful if we can’t do anything with them. This brings us to operations, the small manipulations we can perform on variables and other data. These include things like addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

print(1 + 2)

some_number = 1.2

some_other_number = 3.4

print(some_number + some_other_number)

a_new_number = some_number * some_other_number

print(a_new_number)You will notice that we can print the results of operations, or we can store them in a variable for later use. The output of this code should look like this:

3

4.6

4.08

Python is even smart enough to imply what something like addition or multiplication could mean on a string!

last_name = "Deckard"

first_name = "Rick"

print(first_name + " " + last_name) # Print out full name in order

print(5 * last_name) # Print last_name 5 timesThe first print adds first_name to a space to last_name and

prints it. The second prints last_name 5 times. It should look

something like this:

Rick Deckard

DeckardDeckardDeckardDeckardDeckard

I also (rather

sneakily) introduced a new seemingly minor, but VERY important idea

here: comments! In Python, if you type a #, everything following it on

the same line is not considered part of the code. This is extremely

useful to help you organize and annotate code. It is very easy to

revisit code and completely forget what it does if you have not left

comments.

Finally, many things in Python have different functions associated with them. For the sake of this tutorial, we will consider these operations. Some of the most useful functions are functions that work on strings. The code below illustrates a simple program for getting the GC content of a DNA sequence using some of the functions associated with genes.

dna_seq = "ATCGATCGTACGTACGGTCAGTACGTCAGCTACGTGCATGCATGACGT"

seq_length = len(dna_seq) # Get the lenght of the DNA sequence

gc_count = dna_seq.count("G") + dna_seq.count("C") # Get the total number of G's and C's

print("The percent GC content of the sequence is:")

print( gc_count/seq_length * 100) # Multiply by 100 to convert to percentThis should print the following:

The percent GC content of the sequence is:

52.083333333333336

Another useful function is .index(). This will get the index of the

first occurence of something in your string. For example:

dna_seq = "TCTGATGCAAGCATATAAGCGCAA"

print( dna_seq.index("ATG") )This should print 4 if everything is correct. While quite small,

this deceptively simple program is capable of finding the first start

codon in a DNA sequence! Not bad for only two lines of code!

We have now seen how we can store and manipulate data, but our programs have all been linear, thus far. That is, they go step by step and always do the exact same thing, in the exact same order, no matter how the data changes! This doesn’t offer a lot of flexibility. Enter flow control…

Flow control refers to how we make programs behave differently depending on the conditions the program is run under. We will look at three ways in which we can change the flow of a program: if statements, for loops, and while loops.

An if statement can be used when we want the program to do one thing if something is true, and another if it is not. The most basic if statement is called an if-else. An example is below:

dna_seq = "ATGCTGTCGGCTAGGACTCGCTAGTAC"

if ( dna_seq[0:3] == "ATG" ):

print("This sequence begins with a start codon!")

else:

print("This sequence does not begin with a start codon.")You should see This sequence begins with a start codon! printed to

your screen when you run this code. Try changing the DNA sequence by

changing the first line to this:

dna_seq = "TCACTGTCGGCTAGGACTCGCTAGTAC"Notice that the output has changed? No? It hasn’t? Then you haven’t copied the code correctly, try again.

Before we go on, let’s take a look at one new thing that shows up here: code blocks. Code blocks are how code is organized into logical sections. These are very important! The computer uses code blocks to determine what code to run as part of an if statement, a loop, or a function (something we won’t be covering). A code block consists of all the code that is indented by a tab. Everything within the tabbed section is part of that block. It is standard to use 4 spaces as a tab in Python. The code block ends when it is ‘unindented’.

If statements can also be made more complex, allowing us to handle

situations where we have more than one option we may want to take. Below

we have an example using an elif, short for ‘else if’.

codon = "TAA"

if ( codon == "ATG" ):

print("This is a start codon.")

elif ( codon in ["TAA", "TAG", "TGA"] ):

print(" This is a stop codon.")

else:

print("This is neither a stop nor a start codon.")This example will print This is a stop codon.

I also introduced a useful operator here; the in operator. This is

useful for determining if something is contained in a collection of

items, such as a list.

One more point on if statements; you do not need to have an else,

although it is considered good practice to have one. It is very easy to

think that you have covered all cases, when you have actually missed

one. The else will help to catch these unconsidered cases, even if only

to tell you that something happened that you did not expect, such as an

error.

One of the most powerful ways of controlling program flow is by way of a loop. This allows you to use the same bit of code many times over again, which can save a lot of time for a few obvious reasons. The idea behind a for loop is that it incrementally changes some variable that you want to manipulate with each iteration of the loop. Often times, this variable is a number. In Python specifically, this can be done like so:

for i in range(0, 10):

print(i)There are a few things to notice about this snippet of code. Firstly,

notice that it uses code blocks in a similar way to the if statement.

The second thing to notice is the i. This is a variable that will

store some value for each iteration of the loop. In this case, Python

will generate a range from 0 to 10, not including 10, and with each

round of the loop, i will take on one of those values. Try running

this code and take note of what happens.

But that’s not all for loops can do in Python! They can loop over

almost anything that has a logical iterable feeling to it. For

example, the following snippet will iterate over each letter in a sequence and

print any symbol that is not a valid nucleotide (i.e. is one

of A, T, C, or G).

dna_seq = "ATCGCTGACTGCATGCQACTGCATGCAHCATGCAGCY"

valid_dna = "ATCG"

for symbol in dna_seq:

if not ( symbol in valid_dna ):

print(symbol)There are a few new things that I have introduced here. First of all,

notice the use of not. This will check the condition in the if

statement, then take the opposite. So if symbol is in valid_dna,

then we do not want to print it. The second thing to notice is that the

code blocks were nested. What that means is that we can put loops or if

statements within one another!

And now we come to our final tool for controlling the flow of a program, and the final concept we will tackle before we get into building an ORF finder; the while loop.

A while loop combines a condition, just like is done in if statements, with the

ability to loop. At the start of each iteration, it will check to see if

a condition is met. If it is, then it will run through the loop, rinse,

and repeat. The example below will decrement counter by 1 until it hits

0, then it will stop.

counter = 10

while ( counter > 0 ):

print(counter)

counter = counter - 1

print("Done.")We now have all of the tools (and a few extras) that we need to start building an ORF finder! From here on out, this post will be stepping through and building the ORF finder up, bit by bit.

I would like to introduce you to ΦX174 (Phi X 174), a bacteriophage and the first DNA based organism to be sequenced (Sanger et al., 1974)

I would now like to introduce you to its genome:

>gi|9626372|ref|NC_001422.1| Enterobacteria phage phiX174, complete genome

GAGTTTTATCGCTTCCATGACGCAGAAGTTAACACTTTCGGATATTTCTGATGAGTCGAAAAATTATCTTGATAAAGCAGGAATTACTACTGCTTGTTTACGAATTAAATCGAAGTGGACTGCTGGCGGAAAATGAGAAAATTCGACCTATCCTTGCGCAGCTCGAGAAGCTCTTACTTTGCGACCTTTCGCCATCAACTAACGATTCTGTCAAAAACTGACGCGTTGGATGAGGAGAAGTGGCTTAATATGCTTGGCACGTTCGTCAAGGACTGGTTTAGATATGAGTCACATTTTGTTCATGGTAGAGATTCTCTTGTTGACATTTTAAAAGAGCGTGGATTACTATCTGAGTCCGATGCTGTTCAACCACTAATAGGTAAGAAATCATGAGTCAAGTTACTGAACAATCCGTACGTTTCCAGACCGCTTTGGCCTCTATTAAGCTCATTCAGGCTTCTGCCGTTTTGGATTTAACCGAAGATGATTTCGATTTTCTGACGAGTAACAAAGTTTGGATTGCTACTGACCGCTCTCGTGCTCGTCGCTGCGTTGAGGCTTGCGTTTATGGTACGCTGGACTTTGTGGGATACCCTCGCTTTCCTGCTCCTGTTGAGTTTATTGCTGCCGTCATTGCTTATTATGTTCATCCCGTCAACATTCAAACGGCCTGTCTCATCATGGAAGGCGCTGAATTTACGGAAAACATTATTAATGGCGTCGAGCGTCCGGTTAAAGCCGCTGAATTGTTCGCGTTTACCTTGCGTGTACGCGCAGGAAACACTGACGTTCTTACTGACGCAGAAGAAAACGTGCGTCAAAAATTACGTGCGGAAGGAGTGATGTAATGTCTAAAGGTAAAAAACGTTCTGGCGCTCGCCCTGGTCGTCCGCAGCCGTTGCGAGGTACTAAAGGCAAGCGTAAAGGCGCTCGTCTTTGGTATGTAGGTGGTCAACAATTTTAATTGCAGGGGCTTCGGCCCCTTACTTGAGGATAAATTATGTCTAATATTCAAACTGGCGCCGAGCGTATGCCGCATGACCTTTCCCATCTTGGCTTCCTTGCTGGTCAGATTGGTCGTCTTATTACCATTTCAACTACTCCGGTTATCGCTGGCGACTCCTTCGAGATGGACGCCGTTGGCGCTCTCCGTCTTTCTCCATTGCGTCGTGGCCTTGCTATTGACTCTACTGTAGACATTTTTACTTTTTATGTCCCTCATCGTCACGTTTATGGTGAACAGTGGATTAAGTTCATGAAGGATGGTGTTAATGCCACTCCTCTCCCGACTGTTAACACTACTGGTTATATTGACCATGCCGCTTTTCTTGGCACGATTAACCCTGATACCAATAAAATCCCTAAGCATTTGTTTCAGGGTTATTTGAATATCTATAACAACTATTTTAAAGCGCCGTGGATGCCTGACCGTACCGAGGCTAACCCTAATGAGCTTAATCAAGATGATGCTCGTTATGGTTTCCGTTGCTGCCATCTCAAAAACATTTGGACTGCTCCGCTTCCTCCTGAGACTGAGCTTTCTCGCCAAATGACGACTTCTACCACATCTATTGACATTATGGGTCTGCAAGCTGCTTATGCTAATTTGCATACTGACCAAGAACGTGATTACTTCATGCAGCGTTACCATGATGTTATTTCTTCATTTGGAGGTAAAACCTCTTATGACGCTGACAACCGTCCTTTACTTGTCATGCGCTCTAATCTCTGGGCATCTGGCTATGATGTTGATGGAACTGACCAAACGTCGTTAGGCCAGTTTTCTGGTCGTGTTCAACAGACCTATAAACATTCTGTGCCGCGTTTCTTTGTTCCTGAGCATGGCACTATGTTTACTCTTGCGCTTGTTCGTTTTCCGCCTACTGCGACTAAAGAGATTCAGTACCTTAACGCTAAAGGTGCTTTGACTTATACCGATATTGCTGGCGACCCTGTTTTGTATGGCAACTTGCCGCCGCGTGAAATTTCTATGAAGGATGTTTTCCGTTCTGGTGATTCGTCTAAGAAGTTTAAGATTGCTGAGGGTCAGTGGTATCGTTATGCGCCTTCGTATGTTTCTCCTGCTTATCACCTTCTTGAAGGCTTCCCATTCATTCAGGAACCGCCTTCTGGTGATTTGCAAGAACGCGTACTTATTCGCCACCATGATTATGACCAGTGTTTCCAGTCCGTTCAGTTGTTGCAGTGGAATAGTCAGGTTAAATTTAATGTGACCGTTTATCGCAATCTGCCGACCACTCGCGATTCAATCATGACTTCGTGATAAAAGATTGAGTGTGAGGTTATAACGCCGAAGCGGTAAAAATTTTAATTTTTGCCGCTGAGGGGTTGACCAAGCGAAGCGCGGTAGGTTTTCTGCTTAGGAGTTTAATCATGTTTCAGACTTTTATTTCTCGCCATAATTCAAACTTTTTTTCTGATAAGCTGGTTCTCACTTCTGTTACTCCAGCTTCTTCGGCACCTGTTTTACAGACACCTAAAGCTACATCGTCAACGTTATATTTTGATAGTTTGACGGTTAATGCTGGTAATGGTGGTTTTCTTCATTGCATTCAGATGGATACATCTGTCAACGCCGCTAATCAGGTTGTTTCTGTTGGTGCTGATATTGCTTTTGATGCCGACCCTAAATTTTTTGCCTGTTTGGTTCGCTTTGAGTCTTCTTCGGTTCCGACTACCCTCCCGACTGCCTATGATGTTTATCCTTTGAATGGTCGCCATGATGGTGGTTATTATACCGTCAAGGACTGTGTGACTATTGACGTCCTTCCCCGTACGCCGGGCAATAACGTTTATGTTGGTTTCATGGTTTGGTCTAACTTTACCGCTACTAAATGCCGCGGATTGGTTTCGCTGAATCAGGTTATTAAAGAGATTATTTGTCTCCAGCCACTTAAGTGAGGTGATTTATGTTTGGTGCTATTGCTGGCGGTATTGCTTCTGCTCTTGCTGGTGGCGCCATGTCTAAATTGTTTGGAGGCGGTCAAAAAGCCGCCTCCGGTGGCATTCAAGGTGATGTGCTTGCTACCGATAACAATACTGTAGGCATGGGTGATGCTGGTATTAAATCTGCCATTCAAGGCTCTAATGTTCCTAACCCTGATGAGGCCGCCCCTAGTTTTGTTTCTGGTGCTATGGCTAAAGCTGGTAAAGGACTTCTTGAAGGTACGTTGCAGGCTGGCACTTCTGCCGTTTCTGATAAGTTGCTTGATTTGGTTGGACTTGGTGGCAAGTCTGCCGCTGATAAAGGAAAGGATACTCGTGATTATCTTGCTGCTGCATTTCCTGAGCTTAATGCTTGGGAGCGTGCTGGTGCTGATGCTTCCTCTGCTGGTATGGTTGACGCCGGATTTGAGAATCAAAAAGAGCTTACTAAAATGCAACTGGACAATCAGAAAGAGATTGCCGAGATGCAAAATGAGACTCAAAAAGAGATTGCTGGCATTCAGTCGGCGACTTCACGCCAGAATACGAAAGACCAGGTATATGCACAAAATGAGATGCTTGCTTATCAACAGAAGGAGTCTACTGCTCGCGTTGCGTCTATTATGGAAAACACCAATCTTTCCAAGCAACAGCAGGTTTCCGAGATTATGCGCCAAATGCTTACTCAAGCTCAAACGGCTGGTCAGTATTTTACCAATGACCAAATCAAAGAAATGACTCGCAAGGTTAGTGCTGAGGTTGACTTAGTTCATCAGCAAACGCAGAATCAGCGGTATGGCTCTTCTCATATTGGCGCTACTGCAAAGGATATTTCTAATGTCGTCACTGATGCTGCTTCTGGTGTGGTTGATATTTTTCATGGTATTGATAAAGCTGTTGCCGATACTTGGAACAATTTCTGGAAAGACGGTAAAGCTGATGGTATTGGCTCTAATTTGTCTAGGAAATAACCGTCAGGATTGACACCCTCCCAATTGTATGTTTTCATGCCTCCAAATCTTGGAGGCTTTTTTATGGTTCGTTCTTATTACCCTTCTGAATGTCACGCTGATTATTTTGACTTTGAGCGTATCGAGGCTCTTAAACCTGCTATTGAGGCTTGTGGCATTTCTACTCTTTCTCAATCCCCAATGCTTGGCTTCCATAAGCAGATGGATAACCGCATCAAGCTCTTGGAAGAGATTCTGTCTTTTCGTATGCAGGGCGTTGAGTTCGATAATGGTGATATGTATGTTGACGGCCATAAGGCTGCTTCTGACGTTCGTGATGAGTTTGTATCTGTTACTGAGAAGTTAATGGATGAATTGGCACAATGCTACAATGTGCTCCCCCAACTTGATATTAATAACACTATAGACCACCGCCCCGAAGGGGACGAAAAATGGTTTTTAGAGAACGAGAAGACGGTTACGCAGTTTTGCCGCAAGCTGGCTGCTGAACGCCCTCTTAAGGATATTCGCGATGAGTATAATTACCCCAAAAAGAAAGGTATTAAGGATGAGTGTTCAAGATTGCTGGAGGCCTCCACTATGAAATCGCGTAGAGGCTTTGCTATTCAGCGTTTGATGAATGCAATGCGACAGGCTCATGCTGATGGTTGGTTTATCGTTTTTGACACTCTCACGTTGGCTGACGACCGATTAGAGGCGTTTTATGATAATCCCAATGCTTTGCGTGACTATTTTCGTGATATTGGTCGTATGGTTCTTGCTGCCGAGGGTCGCAAGGCTAATGATTCACACGCCGACTGCTATCAGTATTTTTGTGTGCCTGAGTATGGTACAGCTAATGGCCGTCTTCATTTCCATGCGGTGCACTTTATGCGGACACTTCCTACAGGTAGCGTTGACCCTAATTTTGGTCGTCGGGTACGCAATCGCCGCCAGTTAAATAGCTTGCAAAATACGTGGCCTTATGGTTACAGTATGCCCATCGCAGTTCGCTACACGCAGGACGCTTTTTCACGTTCTGGTTGGTTGTGGCCTGTTGATGCTAAAGGTGAGCCGCTTAAAGCTACCAGTTATATGGCTGTTGGTTTCTATGTGGCTAAATACGTTAACAAAAAGTCAGATATGGACCTTGCTGCTAAAGGTCTAGGAGCTAAAGAATGGAACAACTCACTAAAAACCAAGCTGTCGCTACTTCCCAAGAAGCTGTTCAGAATCAGAATGAGCCGCAACTTCGGGATGAAAATGCTCACAATGACAAATCTGTCCACGGAGTGCTTAATCCAACTTACCAAGCTGGGTTACGACGCGACGCCGTTCAACCAGATATTGAAGCAGAACGCAAAAAGAGAGATGAGATTGAGGCTGGGAAAAGTTACTGTAGCCGACGTTTTGGCGGCGCAACCTGTGACGACAAATCTGCTCAAATTTATGCGCGCTTCGATAAAAATGATTGGCGTATCCAACCTGCA

This is a tiny genome! Only about 5kb and encoding only 11 proteins. But this is why it’s a perfect genome to learn with!

To start off, we will copy the sequence into a variable. In general, you would not just copy the sequence like this, you would typically use Pythons’s file I/O, but for the sake of simplicity, just copy it into a variable like so:

phi_genome = "GAGTTTTATCGCTTCCATGACGCAGAAGTTAACACTTTCGGATATTTCTGATGAGTCGAAAAATTATCTTGATAAAGCAGGAATTACTACTGCTTGTTTACGAATTAAATCGAAGTGGACTGCTGGCGGAAAATGAGAAAATTCGACCTATCCTTGCGCAGCTCGAGAAGCTCTTACTTTGCGACCTTTCGCCATCAACTAACGATTCTGTCAAAAACTGACGCGTTGGATGAGGAGAAGTGGCTTAATATGCTTGGCACGTTCGTCAAGGACTGGTTTAGATATGAGTCACATTTTGTTCATGGTAGAGATTCTCTTGTTGACATTTTAAAAGAGCGTGGATTACTATCTGAGTCCGATGCTGTTCAACCACTAATAGGTAAGAAATCATGAGTCAAGTTACTGAACAATCCGTACGTTTCCAGACCGCTTTGGCCTCTATTAAGCTCATTCAGGCTTCTGCCGTTTTGGATTTAACCGAAGATGATTTCGATTTTCTGACGAGTAACAAAGTTTGGATTGCTACTGACCGCTCTCGTGCTCGTCGCTGCGTTGAGGCTTGCGTTTATGGTACGCTGGACTTTGTGGGATACCCTCGCTTTCCTGCTCCTGTTGAGTTTATTGCTGCCGTCATTGCTTATTATGTTCATCCCGTCAACATTCAAACGGCCTGTCTCATCATGGAAGGCGCTGAATTTACGGAAAACATTATTAATGGCGTCGAGCGTCCGGTTAAAGCCGCTGAATTGTTCGCGTTTACCTTGCGTGTACGCGCAGGAAACACTGACGTTCTTACTGACGCAGAAGAAAACGTGCGTCAAAAATTACGTGCGGAAGGAGTGATGTAATGTCTAAAGGTAAAAAACGTTCTGGCGCTCGCCCTGGTCGTCCGCAGCCGTTGCGAGGTACTAAAGGCAAGCGTAAAGGCGCTCGTCTTTGGTATGTAGGTGGTCAACAATTTTAATTGCAGGGGCTTCGGCCCCTTACTTGAGGATAAATTATGTCTAATATTCAAACTGGCGCCGAGCGTATGCCGCATGACCTTTCCCATCTTGGCTTCCTTGCTGGTCAGATTGGTCGTCTTATTACCATTTCAACTACTCCGGTTATCGCTGGCGACTCCTTCGAGATGGACGCCGTTGGCGCTCTCCGTCTTTCTCCATTGCGTCGTGGCCTTGCTATTGACTCTACTGTAGACATTTTTACTTTTTATGTCCCTCATCGTCACGTTTATGGTGAACAGTGGATTAAGTTCATGAAGGATGGTGTTAATGCCACTCCTCTCCCGACTGTTAACACTACTGGTTATATTGACCATGCCGCTTTTCTTGGCACGATTAACCCTGATACCAATAAAATCCCTAAGCATTTGTTTCAGGGTTATTTGAATATCTATAACAACTATTTTAAAGCGCCGTGGATGCCTGACCGTACCGAGGCTAACCCTAATGAGCTTAATCAAGATGATGCTCGTTATGGTTTCCGTTGCTGCCATCTCAAAAACATTTGGACTGCTCCGCTTCCTCCTGAGACTGAGCTTTCTCGCCAAATGACGACTTCTACCACATCTATTGACATTATGGGTCTGCAAGCTGCTTATGCTAATTTGCATACTGACCAAGAACGTGATTACTTCATGCAGCGTTACCATGATGTTATTTCTTCATTTGGAGGTAAAACCTCTTATGACGCTGACAACCGTCCTTTACTTGTCATGCGCTCTAATCTCTGGGCATCTGGCTATGATGTTGATGGAACTGACCAAACGTCGTTAGGCCAGTTTTCTGGTCGTGTTCAACAGACCTATAAACATTCTGTGCCGCGTTTCTTTGTTCCTGAGCATGGCACTATGTTTACTCTTGCGCTTGTTCGTTTTCCGCCTACTGCGACTAAAGAGATTCAGTACCTTAACGCTAAAGGTGCTTTGACTTATACCGATATTGCTGGCGACCCTGTTTTGTATGGCAACTTGCCGCCGCGTGAAATTTCTATGAAGGATGTTTTCCGTTCTGGTGATTCGTCTAAGAAGTTTAAGATTGCTGAGGGTCAGTGGTATCGTTATGCGCCTTCGTATGTTTCTCCTGCTTATCACCTTCTTGAAGGCTTCCCATTCATTCAGGAACCGCCTTCTGGTGATTTGCAAGAACGCGTACTTATTCGCCACCATGATTATGACCAGTGTTTCCAGTCCGTTCAGTTGTTGCAGTGGAATAGTCAGGTTAAATTTAATGTGACCGTTTATCGCAATCTGCCGACCACTCGCGATTCAATCATGACTTCGTGATAAAAGATTGAGTGTGAGGTTATAACGCCGAAGCGGTAAAAATTTTAATTTTTGCCGCTGAGGGGTTGACCAAGCGAAGCGCGGTAGGTTTTCTGCTTAGGAGTTTAATCATGTTTCAGACTTTTATTTCTCGCCATAATTCAAACTTTTTTTCTGATAAGCTGGTTCTCACTTCTGTTACTCCAGCTTCTTCGGCACCTGTTTTACAGACACCTAAAGCTACATCGTCAACGTTATATTTTGATAGTTTGACGGTTAATGCTGGTAATGGTGGTTTTCTTCATTGCATTCAGATGGATACATCTGTCAACGCCGCTAATCAGGTTGTTTCTGTTGGTGCTGATATTGCTTTTGATGCCGACCCTAAATTTTTTGCCTGTTTGGTTCGCTTTGAGTCTTCTTCGGTTCCGACTACCCTCCCGACTGCCTATGATGTTTATCCTTTGAATGGTCGCCATGATGGTGGTTATTATACCGTCAAGGACTGTGTGACTATTGACGTCCTTCCCCGTACGCCGGGCAATAACGTTTATGTTGGTTTCATGGTTTGGTCTAACTTTACCGCTACTAAATGCCGCGGATTGGTTTCGCTGAATCAGGTTATTAAAGAGATTATTTGTCTCCAGCCACTTAAGTGAGGTGATTTATGTTTGGTGCTATTGCTGGCGGTATTGCTTCTGCTCTTGCTGGTGGCGCCATGTCTAAATTGTTTGGAGGCGGTCAAAAAGCCGCCTCCGGTGGCATTCAAGGTGATGTGCTTGCTACCGATAACAATACTGTAGGCATGGGTGATGCTGGTATTAAATCTGCCATTCAAGGCTCTAATGTTCCTAACCCTGATGAGGCCGCCCCTAGTTTTGTTTCTGGTGCTATGGCTAAAGCTGGTAAAGGACTTCTTGAAGGTACGTTGCAGGCTGGCACTTCTGCCGTTTCTGATAAGTTGCTTGATTTGGTTGGACTTGGTGGCAAGTCTGCCGCTGATAAAGGAAAGGATACTCGTGATTATCTTGCTGCTGCATTTCCTGAGCTTAATGCTTGGGAGCGTGCTGGTGCTGATGCTTCCTCTGCTGGTATGGTTGACGCCGGATTTGAGAATCAAAAAGAGCTTACTAAAATGCAACTGGACAATCAGAAAGAGATTGCCGAGATGCAAAATGAGACTCAAAAAGAGATTGCTGGCATTCAGTCGGCGACTTCACGCCAGAATACGAAAGACCAGGTATATGCACAAAATGAGATGCTTGCTTATCAACAGAAGGAGTCTACTGCTCGCGTTGCGTCTATTATGGAAAACACCAATCTTTCCAAGCAACAGCAGGTTTCCGAGATTATGCGCCAAATGCTTACTCAAGCTCAAACGGCTGGTCAGTATTTTACCAATGACCAAATCAAAGAAATGACTCGCAAGGTTAGTGCTGAGGTTGACTTAGTTCATCAGCAAACGCAGAATCAGCGGTATGGCTCTTCTCATATTGGCGCTACTGCAAAGGATATTTCTAATGTCGTCACTGATGCTGCTTCTGGTGTGGTTGATATTTTTCATGGTATTGATAAAGCTGTTGCCGATACTTGGAACAATTTCTGGAAAGACGGTAAAGCTGATGGTATTGGCTCTAATTTGTCTAGGAAATAACCGTCAGGATTGACACCCTCCCAATTGTATGTTTTCATGCCTCCAAATCTTGGAGGCTTTTTTATGGTTCGTTCTTATTACCCTTCTGAATGTCACGCTGATTATTTTGACTTTGAGCGTATCGAGGCTCTTAAACCTGCTATTGAGGCTTGTGGCATTTCTACTCTTTCTCAATCCCCAATGCTTGGCTTCCATAAGCAGATGGATAACCGCATCAAGCTCTTGGAAGAGATTCTGTCTTTTCGTATGCAGGGCGTTGAGTTCGATAATGGTGATATGTATGTTGACGGCCATAAGGCTGCTTCTGACGTTCGTGATGAGTTTGTATCTGTTACTGAGAAGTTAATGGATGAATTGGCACAATGCTACAATGTGCTCCCCCAACTTGATATTAATAACACTATAGACCACCGCCCCGAAGGGGACGAAAAATGGTTTTTAGAGAACGAGAAGACGGTTACGCAGTTTTGCCGCAAGCTGGCTGCTGAACGCCCTCTTAAGGATATTCGCGATGAGTATAATTACCCCAAAAAGAAAGGTATTAAGGATGAGTGTTCAAGATTGCTGGAGGCCTCCACTATGAAATCGCGTAGAGGCTTTGCTATTCAGCGTTTGATGAATGCAATGCGACAGGCTCATGCTGATGGTTGGTTTATCGTTTTTGACACTCTCACGTTGGCTGACGACCGATTAGAGGCGTTTTATGATAATCCCAATGCTTTGCGTGACTATTTTCGTGATATTGGTCGTATGGTTCTTGCTGCCGAGGGTCGCAAGGCTAATGATTCACACGCCGACTGCTATCAGTATTTTTGTGTGCCTGAGTATGGTACAGCTAATGGCCGTCTTCATTTCCATGCGGTGCACTTTATGCGGACACTTCCTACAGGTAGCGTTGACCCTAATTTTGGTCGTCGGGTACGCAATCGCCGCCAGTTAAATAGCTTGCAAAATACGTGGCCTTATGGTTACAGTATGCCCATCGCAGTTCGCTACACGCAGGACGCTTTTTCACGTTCTGGTTGGTTGTGGCCTGTTGATGCTAAAGGTGAGCCGCTTAAAGCTACCAGTTATATGGCTGTTGGTTTCTATGTGGCTAAATACGTTAACAAAAAGTCAGATATGGACCTTGCTGCTAAAGGTCTAGGAGCTAAAGAATGGAACAACTCACTAAAAACCAAGCTGTCGCTACTTCCCAAGAAGCTGTTCAGAATCAGAATGAGCCGCAACTTCGGGATGAAAATGCTCACAATGACAAATCTGTCCACGGAGTGCTTAATCCAACTTACCAAGCTGGGTTACGACGCGACGCCGTTCAACCAGATATTGAAGCAGAACGCAAAAAGAGAGATGAGATTGAGGCTGGGAAAAGTTACTGTAGCCGACGTTTTGGCGGCGCAACCTGTGACGACAAATCTGCTCAAATTTATGCGCGCTTCGATAAAAATGATTGGCGTATCCAACCTGCA"If you do want to try this using file I/O, or just to make a copy and paste easier, the fasta file is available here.

Now that we have a sequence in place, let’s plan out our program. It is always a good idea to think about your problem before you even sit down at the keyboard!

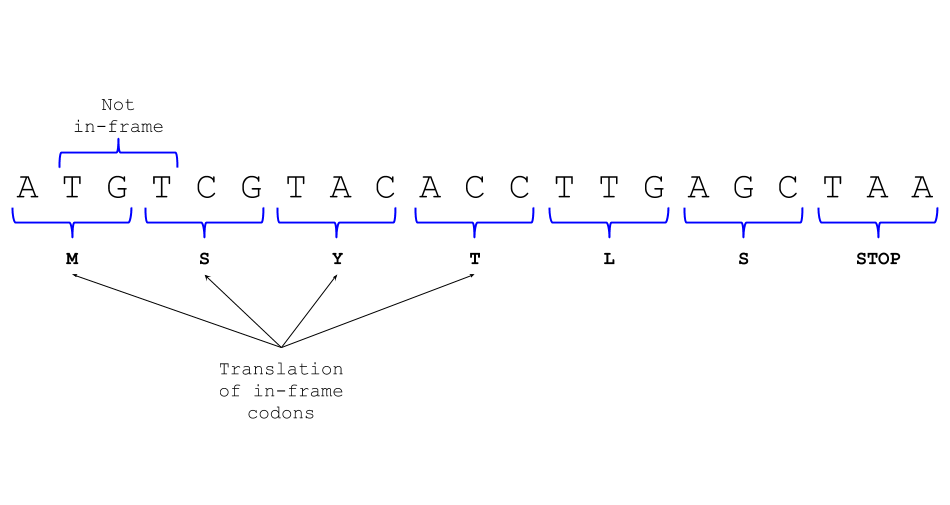

An ORF

finder is a program that looks for open reading frames (ORFs). These are

sequences read three nucleotides at a time. Each triplet is called a

codon and can be translated into a single amino acid. The trick here is

that each triplet needs to be in frame with a start codon. That is, no

two adjacent codons can overlap. Open reading frames must also finish

with a stop codon, which represents the very end of the frame. Start

codons are the sequence “ATG”, while stop codons can be any of “TAG”,

“TAA”, or “TGA”. Every sequence has six possible frames: Three on the

forward strand, and three on the reverse. The first frame is illustrated

below, starting at A. In this case, the first frame is also an ORF,

since it starts with a start codon and ends with a stop codon.

The second frame would start at the first T and the

third at the first G.

Finding an ORF can be a relatively complex task, since we have to consider both the forward and reverse strand of DNA, we have to consider whether or not the genome is cyclic, and we need to think about where the start and stop codons are. This gets even more complicated in Eurkaryotic genomes, where we have to think about splicing and other post-transcriptional modifications that might change the sequence before it is translated! But since we are just starting, we will only consider a few of these aspects for now. I will include a more complicated ORF finder for you to download and look at, in your own time, at the end of this post.

To solve the ORF problem, we will use a common algorithmic techniqe called a ‘sliding window’. We will create a window that looks at three nucleotides at a time and slides along the entire genome. To further simplify this, we are just going to look for the first sequence, and we won’t bother looking for the start codon, just the stop codon.

This image should clarify the conceptual idea of the the sliding window. The first part that we will implement is the sliding part. To do this, we will use a loop. We have seen how to iterate over a string with a for loop, but it turns out that a while loop will serve us better here. This will become clear once we add in a window. We will also want a variable to help us keep track of where in the sequence we are. Something like this will do the trick:

position = 0 # Start at position 0

while ( position < len(phi_genome)-2 ):

...

position = position + 3 # Don't forget this, or your loop will never end!One thing to note here is that we have to end a little bit early, hence

the -2 in our condition. This is because the last codon does not start

at the very end of the sequence, but at the third last nucleotide. We

are also incrementing our position tracker by 3, this means that every

time we change position, it will point to the start of an in-frame codon.

We will now replace the ... with the code to get our sliding

window. We will also change this code to print out each codon.

position = 0

while ( position < len(phi_genome)-2 ):

codon = phi_genome[position:(position+3)]

print(codon)

position = position + 3We now have the genome’s first reading frame printing one codon at a

time, this is a great start! The next thing to do is to look for codons

of interest, in particular, we want to find stop codons. To do this,

let’s add a list called stop_codons, and check to see if each

codon is in this list. Your code should look like this now:

stop_codons = ["TAG", "TAA", "TGA"]

position = 0

while ( position < len(phi_genome)-2 ):

codon = phi_genome[position:(position+3)]

if codon in stop_codons:

print(codon + "----> STOP")

else:

print(codon)

position = position + 3This is looking better, but there are a few problems that stand out from glancing through the output. Many of these putative open reading frames seem very short, which makes them a little unbelievable as candidates for proteins. To account for this, we will start by only keeping track of putative ORFs that are sufficiently long. After each STOP codon, we will reset the length counter and start counting a new ORF. The code should look something like this:

stop_codons = ["TAG", "TAA", "TGA"]

position = 0

orf_length = 0

while ( position < len(phi_genome)-2 ):

codon = phi_genome[position:(position+3)]

if codon in stop_codons:

print(codon + "----> STOP")

if ( orf_length > 100 ):

print("----------LONG ORF----------")

orf_length = 0 # Reset the ORF length, we are done with the current frame

else:

print(codon)

orf_length = orf_length + 3

position = position + 3This code will print out a message whenever it gets to an ORF that is more than 100 nucleotides long. These new ORFs are looking a little better, but the output is still cluddered and we still have to read over the input by hand to find them. On top of it, the codons are all printed individually, which may not be the best way to look at them. We will now change our code to collect the codons into one string, and print out the string on a single line, only if it is sufficiently long!

stop_codons = ["TAG", "TAA", "TGA"]

position = 0

orf_length = 0

orf_sequence = "" # Create an initial empty string

while ( position < len(phi_genome)-2 ):

codon = phi_genome[position:(position+3)]

if codon in stop_codons:

if ( orf_length > 100 ):

print("") # Print a blank line to make things easier to read

print(">a_long_orf") # We can even print the sequence with a FASTA header

print(orf_sequence)

orf_length = 0 # Reset the ORF length, we are done with the current frame

orf_sequence = "" # We also need to reset the sequence now

else:

orf_sequence = orf_sequence + codon

orf_length = orf_length + 3

position = position + 3This looks much better! And the sequences are already in FASTA format to boot! This means that they are in a standard format and ready to be further analyzed. Let’s try to follow through with some analysis.

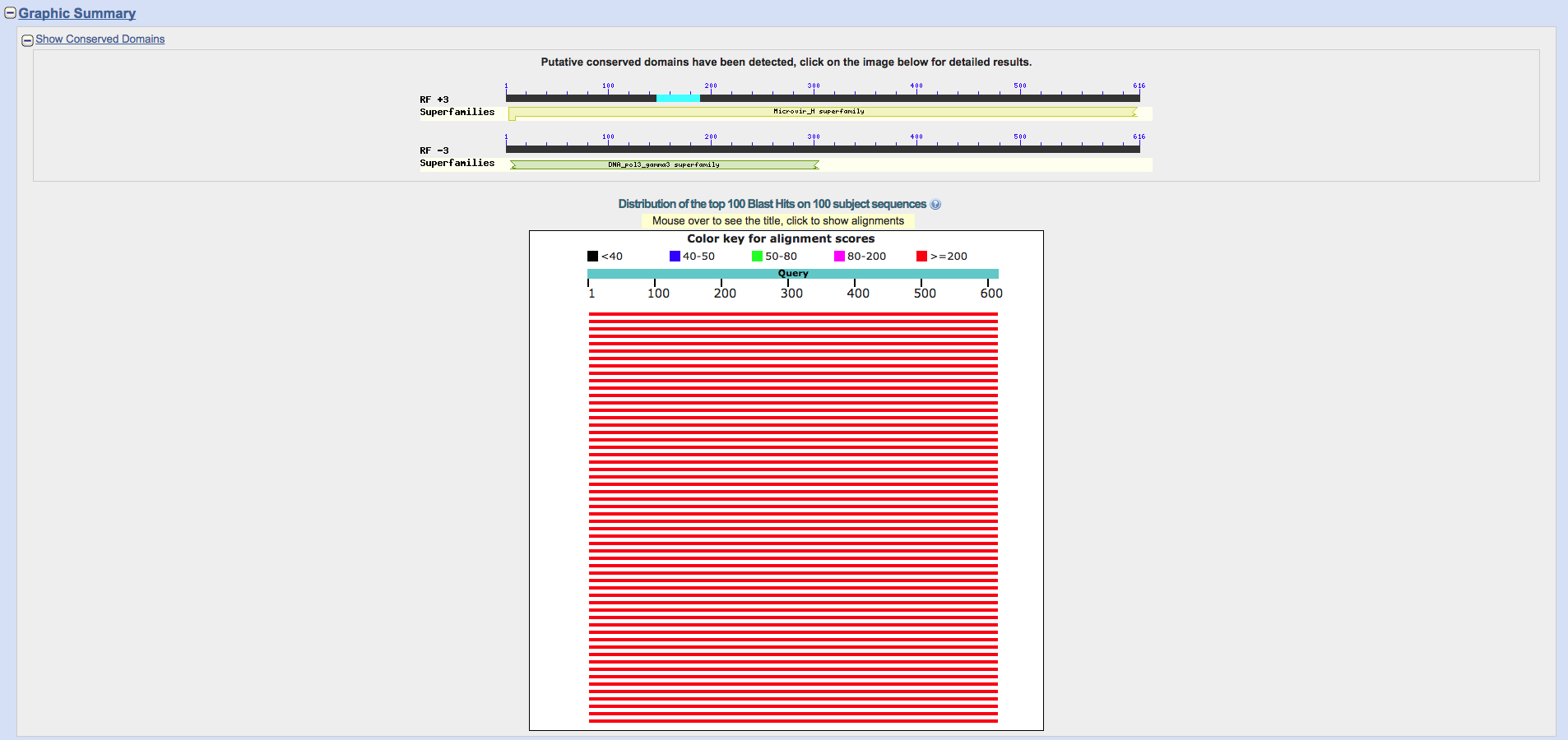

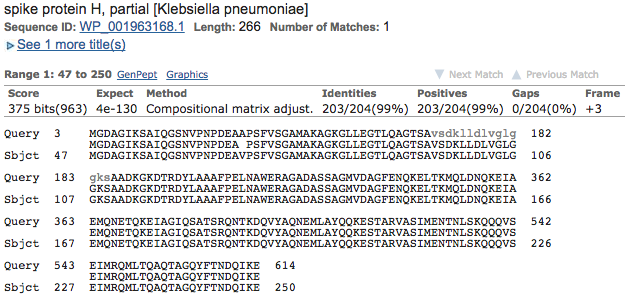

We can now copy one of these sequences into a program like BLAST’s blastx to see if we find anything of interest. With a bit of luck, we should get some good hits, which may confirm that we have indeed found a real ORF! If your sequence doesn’t find anything, try copying another to see if it gives you any results.

Bingo! Looks like there are quite a few good hits! The best scoring hit is below, and it looks like quite a good alignment too (99% identical, doesn’t get much better than that!)

This concludes the tutorial, but there is still plenty to do and learn. We have barely scratched the surface of what Python is capable of! Below are a few exercises and ideas to practice. Look at the ‘Further Reading’ section below to get some help with the exercises.

Finally, I have included a more complete ORF finder that implements some of the below exercises and uses a few new ideas. This file is commented extensively, so feel free to look through it. It introduces quite a few new ideas, such as classes, functions, and more. This code can be downloaded here.

I hope you found this tutorial beneficial and that it has helped to whet your appetite for coding! If you have any comments or questions, be sure to post them below and I will try my best to get back to you!

It has been some time since I have updated this blog, and I think that largely came down to being uncertain with the direction I wanted to take it in. This, ...

I have been developing a project using the C programming language, and in doing so, I have relearned the frustration that is C development (at times – C is g...

This post is a tutorial that will go from a basic introduction to programming, and finish off with writing a simple ORF finder. If you do not know what that...

Hello, world!